by Eddie Pipkin

Image by 愚木混株 Cdd20 from Pixabay

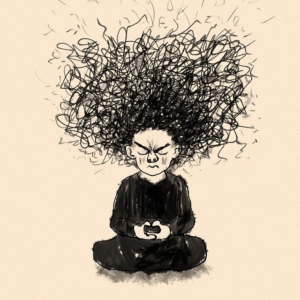

We like to keep things running smoothly. We like to keep things drama free. We like a day characterized by the smiley-faced emoji, not that dude with the grumpy frowny-face. We like a day when there are no hiccups, hangups, or complications. This is nice when it happens, so we do everything we can to try to make it happen – sometimes going so far as to pretend that the not-so-nice things don’t exist, all in an effort to maintain the facade of amiability. Unfortunately, life is complex. Life produces drama. The day (or at least parts of it) often conducts itself with unfavorable emoji vibes. This is the truth. And although as ministry leaders we sometimes try to paper over that truth with feel-good aphorisms and “don’t look behind the curtain” distractions, the most authentic, powerful ministry is the kind that that is willing to embrace life’s difficult complications honestly.

I was thinking about this topic because in short succession last week, the news announced the deaths of two personalities with ‘complicated’ legacies. One was a highly successful actor and the other a highly successful coach, but the deaths of each generated headlines about the complexities of talking about how they would be remembered. Matthew Perry, the Friends actor, had a troublesome history of addiction that clouded the accolades about his affability and terrific sense of humor. Bobby Knight, one of the winningest basketball coaches of all time, had a troublesome temper that clouded his reputation as an on-court leader. Perry’s story was more sympathetic in that his troubles were largely self-destructive, although they certainly impacted those who loved him and worked with him. Knight’s famous tantrums, on the other hand, were indicative of his sometimes abusive treatment of players, officials, and fans, although there were plenty of people willing to stand up and testify that the good in his personality outweighed the bad.

In both cases, writers, reflecting on how these two men would be remembered, acknowledged the necessity of dealing with difficult and uncomfortable issues if these household names were to be discussed at all.

Meanwhile, as the war in Israel which resulted from Hamas’ terrorist attack a month ago spirals into more violence, the rhetoric between competing voices here in the United States has become ever more heated. People concerned about Israeli victims and people concerned about Palestinian civilians have found it hard to engage in civil discourse sharing their differing viewpoints on the emotional topic. A New York Times article, “Across the Echo Chamber, a Quiet Conversation About War and Race,” featured the efforts of two Atlanta-area ladies, Sanidia Oliver and Samara Minkin, to try and understand one another’s perspectives. The sub-title of the article captured the tension:

When two acquaintances in Atlanta sat down to find common ground on the Israel-Hamas war, they found themselves in a painful conversation about race, power and whose suffering is recognized.

There is no happy ending to this exchange in the sense that the two women walked away feeling like they had reached a resolution that ended in happy feelings and high-fives. And yet, they felt that the conversation was worthwhile / important:

They parted with a hug, but both deeply deflated.

The article relates how Oliver felt the conversation had not changed her basic views on the topic:

But she did not regret her time with Ms. Minkin.

“I think it’s a moral responsibility to have conversations with opposing values,” she said later. “I think that’s the only way in a world that is largely driven by greed. In order to make anything better, we just have to talk.”

“Am I changed? Is she changed? Was there any point to this?” Ms. Minkin said she asked herself. “I don’t know that her overall opinion has changed, and I don’t know that my overall opinion has changed. But maybe if we’re all softening at the hard edges, that’s enough?”

Her voice made clear it was a question, not a conclusion.

Of course, as the great Jewish theologians have often stressed, our spiritual journey is about the questions, not the answers. Jesus was fond of great, open-ended questions, too.

When we, as ministry leaders, think of ourselves exclusively as people whose role is to provide definitive answers, to give talking points to those exploring hard topics, we sell ourselves, our churches, and the Gospel short.

Maybe one of our chief roles as ministry leaders, as people whom other people turn to when processing difficult issues, is to model civil ways of navigating difficult discourse.

Of course, many of you, particularly you United Methodist folks (still affiliated or recently otherwise) are thinking, “We are burned out on difficult conversations. Can’t we just have some smooth sailing and time to recuperate?” It’s an honest feeling, but the complexities of the world just keep on coming, whether we want to take some time off or not. And in a world where tough issues are a daily reality, we have a role to help people figure out the balance of troublesome news vs. a productive life lived in joy and to provide them with the spiritual tools to navigate the chaos.

It’s a skill set that younger generations desperately need as well.

Nate Silver, the polling guru, recently noted in his blog how free speech as a basic concept is increasingly eschewed by younger generations. He was writing about college campuses and political speech, primarily, but there are certainly disturbing corollaries in our local churches as congregations become more closely identified with their positions on certain specific culture war topics. We run the risk of becoming “spiritual silos,” linked to very narrow expressions of faith. Of course, there has always been an element of that in denominational sorting, but a freedom to explore differing viewpoints – or certainly at least to share different perspectives and life experiences – may be one of the keys to staying relevant for a younger generation of seekers.

If you want to be known as a community that tackles tough topics, there are some things to remember:

- Don’t publicize ‘tough topics’ as a marketing gimmick, just to grab headlines and attention. If you are going to tackle them, do so in a thoughtful, respectful way whose intent is to increase dialogue, bring people together, promote greater understanding, and seek possible solutions.

- Carefully select leaders who will facilitate such discussions. These are not the venues for your most dramatic or shoot-from-the-hip personalities. These discussions should be led by people with experience, knowledge, and strong reconciliation and listening skills. And they should follow a careful plan for processing the ideas they will explore.

- Commit to providing training for facilitators and participants in healthy dialogue. Whether formal in nature or through the co-reading of solid texts and helpful online material, give leaders and participants the skills they need to pursue complex conversations in healthy ways. (Here’s a starter article from NPR’s Yuki Noguchi on tips for resolving conflicts from great leaders and teachers from history.)

How does your ministry do at facilitating complicated conversations? Do you have regular training to help facilitators and ministry leaders guide people in healthy ways as they are engaging in conversations? Do you publicly emphasize your commitment to being a place where dialogue is encouraged, even difficult dialogue? Does the community know you as a place of shared perspectives, available to help people work through their thoughts and opinions? Share your ideas in the comments section!

Leave A Comment